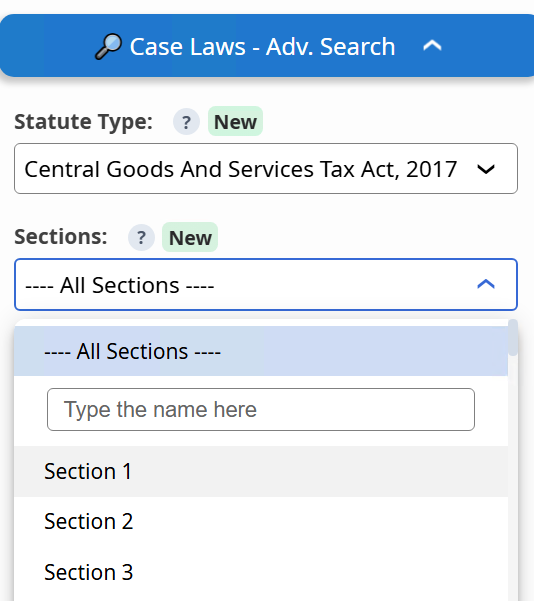

The Persistent Problem of Delay:

This is not unusual in India’s current tax environment for provisional customs assessments to often remain unresolved for years. Such delays have a direct effect on the business development and budget. Companies are required to furnish bank guarantees or bonds and pay differential duties during the pendency of provisional assessments, often resulting in delays that adversely affect the clearance of imported goods. Though the regulatory frame work has evolved over the years with regulations like the Customs (Finalization of Provisional Assessment) Regulation,2018, there are still lacunas and practical inefficiencies that hinder timely finalization of provisional assessment.

The issue is particularly pronounced in cases involving the Special Valuation Branch (SVB). While Circular No. 05/2016-Customs outlines a structured timeline i.e,60 days for importers/exporters to furnish information and up to four months for completing investigations, these deadlines are frequently extended at the discretion of the Chief Commissioner. In practice, this has led to provisional assessments remaining unresolved for years, undermining the intended efficiency of the SVB mechanism

Project import cases have also been facing similar issues. Circular 22/2011 advises finalization of the documents submitted by the importers/exporters within 60 days from the date of submission but this too can be extended upon the discretion of the jurisdictional commissioner. This discretionary power has resulted in inordinate delays despite provision of structural time-limits.

The 2025 Amendment: A Promising Shift

With these challenges becoming apparent, the Finance Bill, 2025 has suggested a substantial amendment of Section 18 of the Customs Act, 1962. The highlight of this reform is the insertion of sub-section (1B) which provides a clear statutory time limit within which a provisional assessment is required to be finalized at two years only and which can be extended by another one year under the discretion of the Principal Commissioner or Commissioner of Customs. It is important to note that the two years period begins with the date of assent on which the Finance Bill, 2025 is passed in the case of already pending cases. This means that the new regime would have retroactive effect and would help in creating efficiency and closure involving cases that remained open.

Sub-section (1C) tightens the framework by defining when the two-year time-frame for concluding provided assessments may be suspended. Such cases are when information on behalf of an authority that is outside India has to be sought in the legal manner, or materials to be assessed have to wait until higher court or tribunal deliver judgment. The record can also be withheld, where the appellate tribunals have ordered an interim stay, or where the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs (CBIC) has directed that a case be kept pending, or where an application has been made awaiting a decision by the Settlement Commission or the Interim Board. The provision by specifying these particular instances prevents the suspension of the statutory deadline to be based on administrative discretion.

In both these situations, the concerned officer must notify the importer/exporter about reasons of non-finalization. The two years would only resume when the suspension period ends. This is to allow flexibilities that would be relaxed over genuine administrative or legal obstacles without compromising the concept of timely resolution.

How Section 18(1C) Supports FTA Origin Verification and Trade Compliance

One of the outstanding characteristics of the 2025 amendments is that they are a direct reaction to the evolving requirements of preferential trade under Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). The verification of the origin of goods is one of the greatest problems with FTA imports because it is required to obtain the benefits of preferential tariffs. This procedure usually necessitates the Indian customs authorities to seek elaborate information or clarification on the part of the officials in the exporting country. This is time consuming and is normally beyond the control of the importer and the Indian authorities.

This issue is addressed in section 18(1C) (a). It explicitly indicates that the two-year limit to complete the provisional assessments is suspended in case of requesting information to an authority outside India in a legal procedure. This is the case that normally occurs in FTA origin verification. The clock in the assessment resumes after the information requested is received. This safeguards importers against unjust punishment of delays that is beyond their control and ensures that the customs officials are not forced to complete their assessment without the required documentation or verification just for the sake of statutory time-frame provided for the purpose of completion of compliance.

This method is particularly opportune, given that India has recently switched to a more generalized standard of a certificate of origin to a proof of origin standard under the CAROTAR Rules, 2025. Customs officials are now able to demand more supporting documents to prove the origin of goods. This is a sign of India trying to avoid abuse of FTAs and adhering to international standards of trade. Section 18(1C) (a) protects the integrity of the FTA system by permitting the suspension of timelines where verification of foreign origin is pending, without compromising fairness or facilitating trade.

This legislative design is consistent with the process in both FTAs and the Customs (Administration of Rules of Origin under Trade Agreements) Rules, 2020 (CAROTAR). In CAROTAR, where no timeframe is provided in an FTA, the exporting nation is supposed to furnish information within 60 days and the Indian customs is supposed to complete verification within 45 days of receipt. Nevertheless, most FTAs do not have strict timelines, or have the possibility of extensions, so domestic statutory flexibility is necessary. Section 18(1C) therefore aligns the domestic law with international obligations so that the verification process under FTAs is not undermined by strict statutory time limits.

Critical Perspective:

Although this suspension mechanism is needed to allow international cooperation and due process, it also creates a possible loophole: in case of departmental delay in requesting the information or in follow-up, the suspension period may be artificially extended. The provision puts a premium on administrative vigilance and transparency. It is thus important that the customs authorities should be able to communicate with the exporting country and the importer in a timely manner and that they should record and report the cause of any delay as required by the amendment. This is good news to businesses as it brings more transparency and security against the arbitrary closure of assessments, but it also highlights the importance of active monitoring of the status of their cases.

Section 18(1C) is a considered legislative reaction to the difficulties of FTA administration. It strikes a balance between the necessity of timely evaluation and the facts of international cooperation, which favor not only the facilitation of trade but also effective compliance. Its efficiency will however be determined by the degree to which customs authorities will be vigilant in enforcing these measures and the speed at which information is requested and acted upon practically.

The Unresolved Concern: What If the Timeline Is Breached?

Despite these welcome changes, a crucial question remains unanswered: What are the consequences if the assessment is not finalized within the prescribed timeframe? The amendment uses the word “shall,” suggesting a mandatory requirement, but does not specify any legal consequence for non-compliance. Indian courts have previously held that the interpretation of “shall” depends on legislative intent and the context of the provision. In some cases, it is treated as mandatory; in others, as directory, especially if strict compliance would defeat the provision’s purpose.

This ambiguity raises practical concerns. Without a deeming provision or automatic consequence, it is unclear whether a provisional assessment would be deemed final after the expiry of the timeline, whether the importer/exporter would be entitled to an automatic refund, or whether the department could still proceed with finalization after the deadline. The absence of clarity may lead to further litigation and uncertainty. Ironically, the very issues the amendment seeks to resolve.

Conclusion: A Step Forward, but Not the Final Word

The 2025 amendment to Section 18 of the Customs Act is a much-needed and progressive reform. The amendment promises to start a new era of certainty, transparency, and clear procedures in finalizing provisional assessments. This will benefit both businesses and revenue authorities. Extending these timelines to pending cases is a forward-thinking move. It shows a real commitment to efficiency and timely resolution of long-standing matters.

The absence of obvious repercussions of not adhering to these timelines is however a significant shortcoming. When this new system gets underway, the true test will be the clarity and uniformity of administrative direction and the readiness of the courts to enforce the intent of the law. Companies should be vigilant, meticulously record their dealings with the customs officials, and be willing to protect their rights in the court of law should the deadlines be flouted.

Thus, the amendment is a major step in the right direction in the Indian customs system but the real test will be the effectiveness of enforcement and judicial interpretations in addressing the crucial question of accountability in case of failure to meet the deadlines. The prospect of change is evident; its success is now dependent on proper implementation and good governance.

TaxTMI

TaxTMI  TaxTMI

TaxTMI