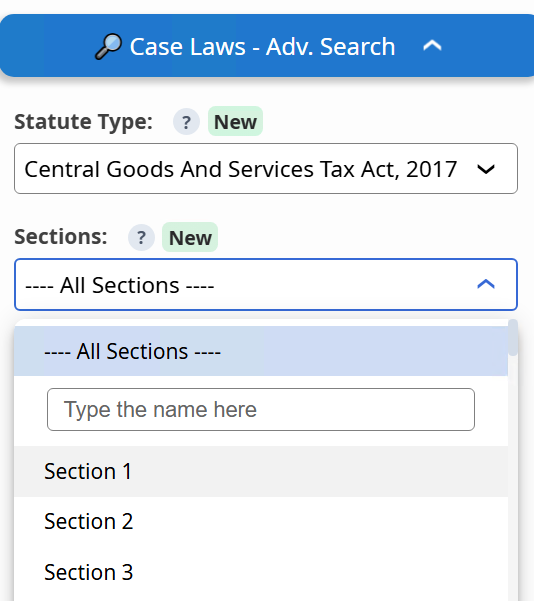

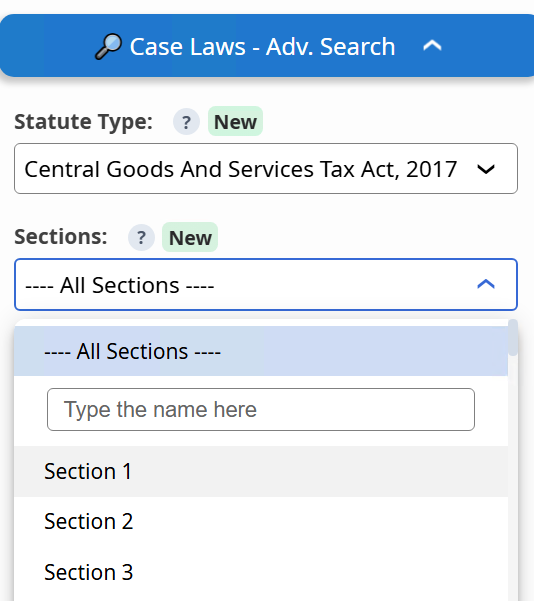

1. Search Case laws by Section / Act / Rule — now available beyond Income Tax. GST and Other Laws Available

2. New: “In Favour Of” filter added in Case Laws.

Try both these filters in Case Laws →

Just a moment...

1. Search Case laws by Section / Act / Rule — now available beyond Income Tax. GST and Other Laws Available

2. New: “In Favour Of” filter added in Case Laws.

Try both these filters in Case Laws →

Press 'Enter' to add multiple search terms. Rules for Better Search

---------------- For section wise search only -----------------

Accuracy Level ~ 90%

Press 'Enter' after typing page number.

Press 'Enter' after typing page number.

No Folders have been created

Are you sure you want to delete "My most important" ?

NOTE:

Press 'Enter' after typing page number.

Press 'Enter' after typing page number.

Don't have an account? Register Here

Press 'Enter' after typing page number.

<h1>Corporate buyer of software license not a 'consumer' under Section 2(1)(d); purchase held commercial, complaint dismissed</h1> SC held the appellant, a corporate/commercial entity, was not a 'consumer' under Section 2(1)(d) of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 for purchasing a ... Consumer Protection - Purchaser of Software License - Commercial Use - Maintainability of complaint - complainant was a consumer as per Section 2(1)(d) of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 or not - HELD THAT:- Sub-clause (i) of Clause (d) of sub-section (1) of Section 2 of the 1986 Act in simple terms provides that “consumer” means any person who buys any goods for a consideration. However, it excludes from its purview a person who obtains such goods for resale or for any commercial purpose. Sub-clause (ii) of Clause (d) of sub-section (1) of Section 2 in simple terms provides that a person who hires or avails of any services for a consideration shall also be a consumer provided such services are not for any commercial purpose. Explanation to clause (d) of sub-section (1) of Section 2 of 1986 Act carves out an exception by clarifying that commercial purpose does not include use by a person of goods bought and used or/ and services availed by him exclusively for the purpose of earning his livelihood by means of self-employment. There is a difference between a self-employed individual and a corporation. The goods purchased by a self-employed individual for self-use for generating livelihood would fall within the explanation even if activity of that person is to generate profits for the purpose of its livelihood. But where a company purchases a software for automating its processes, the object is to maximise profits and, therefore, it would not fall within the explanation of Section 2(1)(d) of the 1986 Act. In Virender Singh v. M/s. Darshana Trading Co. through its partner Sanjay Seth (Dead) & Anr., the complainant, had purchased machines by which the manufacturing of die could be done at cheaper cost and with more precision. As there were defects in the machine, a complaint was filed before the State Commission, wherein the preliminary objection raised was that since the machine was purchased purely for commercial purposes, the complainant is not covered under the definition of a consumer. The objection was sustained by the State Commission and its decision was affirmed by the National Commission. The matter travelled to this Court - In the case on hand also, the complainant had been an established company doing business which bought the product license to automate its processes. In such circumstances, the object of the purchase was not to generate self-employment but to organize its operations with a view to maximise profits - the case of the complainant does not fall within the Explanation to Section 2(1)(d) of the 1986 Act. In the instant case, not only the complainant is a commercial entity, the purchase of goods/ services (i.e., software) from the respondent was with a view to automate the processes of the company which were linked to generation of profit inasmuch as automation of business processes is undertaken not just for better management of the business but to reduce costs and maximise profits. Thus, the transaction of purchase of goods/ services (i.e., software) had a nexus with generation of profits and, therefore, qua that transaction the appellant cannot be considered a consumer as defined in Section 2(1)(d) of the 1986 Act. Both the State Commission as well as the National Commission were justified in holding that the goods /services purchased/ availed by the appellant were for a commercial purpose and therefore the appellant is not a “consumer” as per Section 2(1)(d) of the 1986 Act - Appeal dismissed. ISSUES PRESENTED AND CONSIDERED 1. Whether a purchaser of a software product/license who is an incorporated company qualifies as a 'consumer' under Section 2(1)(d) of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 where the software is acquired to automate and manage business processes. 2. Whether purchase/availing of goods or services by a commercial entity for internal use, including for improving business management and efficiency, constitutes acquisition 'for any commercial purpose' and thus excludes the purchaser from the definition of 'consumer'. 3. The scope and application of the Explanation to Section 2(1)(d) excluding from 'commercial purpose' use of goods/services for earning livelihood by self-employment, and whether that Explanation can extend to incorporated commercial entities. ISSUE-WISE DETAILED ANALYSIS Issue 1: Whether an incorporated company purchasing software for internal business automation is a 'consumer' under Section 2(1)(d) Legal framework: Section 2(1)(d) defines 'consumer' to include purchasers or users of goods or services for consideration, but excludes persons obtaining goods for resale or for any commercial purpose; the Explanation excludes from 'commercial purpose' goods/services used exclusively for earning livelihood by self-employment. Definition of 'person' in Section 2(1)(m) is inclusive and contemplates juristic persons. Precedent treatment: The Court relied on Karnataka Power Transmission Corp. to confirm that a company is a 'person' within the Act and may fall within the definition of 'consumer' depending on facts. Lilavati Kirtilal Mehta Medical Trust was followed for principles to determine 'commercial purpose'. Sunil Kohli and related authorities were considered and distinguished on facts where individuals sought premises for self-employment. Harsolia Motors (National Insurance Co. v. Harsolia Motors) was analyzed for its guidance on the profit-nexus test and illustrations. Interpretation and reasoning: The Court reiterated that identity (e.g., being a company) and transaction value are not conclusive; the dominant purpose of the transaction is determinative. The relevant test is whether the purchase/service has a close and direct nexus with profit-generating activity. Where an established commercial enterprise purchases software to automate processes with the object of reducing costs and maximising profits, the dominant purpose is commercial. The Explanation for self-employment is inapplicable to commercial corporations whose purchase aims to augment business efficiency and profit. Ratio vs. Obiter: Ratio - a company purchasing software to automate business processes that are linked to profit-generation is not a 'consumer' under Section 2(1)(d). Obiter - illustrations drawn from prior cases (e.g., refrigerators/air-conditioners for comfort) serve as explanatory examples but do not change the dominant-purpose test. Conclusion: The Court concluded that an incorporated company that purchased the software license to automate its import/export operations (functions directly tied to profit-generation) did not qualify as a 'consumer' under Section 2(1)(d) of the 1986 Act. Issue 2: Whether acquisition of goods/services for internal business convenience or better management can still be 'commercial purpose' excluding consumer protection Legal framework: Section 2(1)(d) excludes goods/services obtained 'for any commercial purpose'; the Explanation narrows 'commercial purpose' to exclude self-employment where goods/services are used exclusively to earn livelihood. Precedent treatment: Lilavati provides broad principles: commercial purpose ordinarily includes manufacturing/industrial activity and business-to-business transactions; the dominant purpose test applies. Harsolia Motors elucidates that commercial purpose means activities directly intended to generate profit, while Harsolia also recognizes that insurance services may be non-commercial due to indemnificatory nature. Sunil Kohli and Paramount Digital were distinguished on facts concerning self-employment versus established commercial operations. Virender Singh and Paramount were applied to distinguish self-employment purchases from purchases to expand an existing commercial business. Interpretation and reasoning: The Court emphasized that convenience/management-improvement alone does not automatically render a transaction non-commercial if the improvement has a direct nexus to profit-generation (cost reduction, efficiency, business augmentation). The determination must be fact-specific, assessing nature of goods/services and purpose. The Court rejected a broad construction that would bring routine B2B transactions within consumer fora and thereby frustrate the Act's purpose. Ratio vs. Obiter: Ratio - where goods/services acquired for better management/efficiency have a direct nexus to profit-generation, the transaction is a commercial purpose and excludes consumer status. Obiter - the commentary that insurance services may be non-commercial because they secure against loss rather than generate profit was explanatory to Harsolia Motors and not dispositive for other service types. Conclusion: Acquisition of goods or services for internal convenience/management that is directly linked to profit-generation is a commercial purpose and excludes the purchaser from being a 'consumer'; each case requires fact-specific application of the dominant-purpose test. Issue 3: Scope of the Explanation excluding self-employment and its applicability to companies Legal framework: Explanation to Section 2(1)(d) provides that 'commercial purpose' does not include use by a person of goods bought and used by him and services availed by him exclusively for the purpose of earning his livelihood by means of self-employment. Precedent treatment: Sunil Kohli, Laxmi Engineering Works, Cheema Engineering and Paramount Digital illustrate situations where self-employed individuals or unemployed persons seeking self-employment fall within the Explanation and thus qualify as consumers. Karnataka Power Transmission confirms companies are 'persons.' Virender Singh clarifies that small-scale commercial ventures run by businesses do not automatically convert purchases into self-employment for purposes of the Explanation. Interpretation and reasoning: The Court distinguished self-employment by individuals from corporate/commercial enterprise activity. The Explanation is directed at persons who use goods/services exclusively to earn livelihood by self-employment (typically natural persons). A company's purchase aimed at organizing operations to maximise profits is not 'self-employment' within the meaning of the Explanation; therefore the Explanation does not rescue such corporate purchases from being treated as commercial. Ratio vs. Obiter: Ratio - the Explanation is not intended to extend to corporate/commercial purchases aimed at profit maximisation; it protects self-employed persons whose acquisitions are exclusively for earning their livelihood. Obiter - discussion of differences between self-employed individuals and corporations clarifies application but does not expand the Explanation beyond its textual bounds. Conclusion: The Explanation to Section 2(1)(d) excluding self-employment does not apply to an incorporated company purchasing software to automate commercial operations; such purchases remain within 'commercial purpose' and exclude consumer protection. Overall Conclusion The Court upheld that where an established commercial entity purchases software whose purpose is to automate business processes with a close and direct nexus to profit-generation, the transaction is for a commercial purpose and the purchaser does not qualify as a 'consumer' under Section 2(1)(d) of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986; accordingly, complaints based on such transactions are not maintainable under the Act. The Court affirmed prior principles requiring a fact-specific dominant-purpose inquiry and confirmed that companies remain capable of being consumers only where purchases lack a profit-generating nexus, whereas the Explanation for self-employment protects natural persons or self-employed acquisitions and does not extend to corporate profit-oriented purchases.